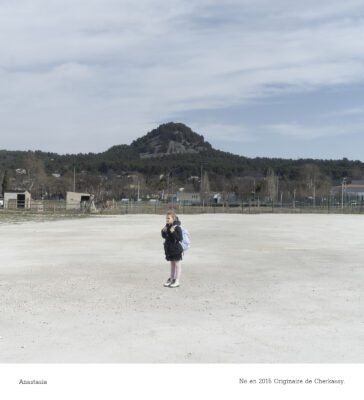

A Propos

24 février 2022, la Russie lance une offensive militaire contre l’Ukraine, tentant de l’envahir.

Des milliers d’Ukrainiens quittent leur pays en quête d’une terre d’asile. La France est l’une d’elle.

Juillet 2022, je quitte Paris pour m’installer à Nice. Au même moment une famille Ukrainienne fuyant la guerre emménage sur le palier d’en face, mes nouveaux voisins. Cette rencontre m’a touché en me confrontant directement à la condition de ces personnes, obligés de fuir leur pays, leurs proches, leurs racines, leur quotidien.

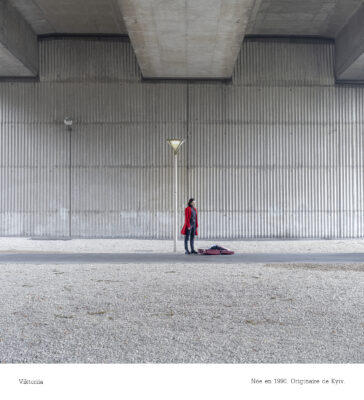

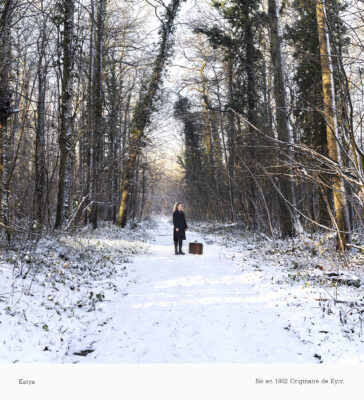

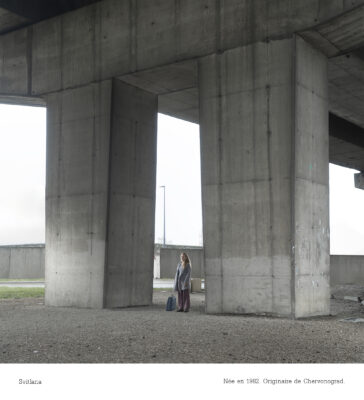

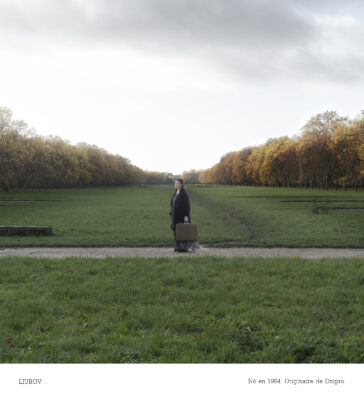

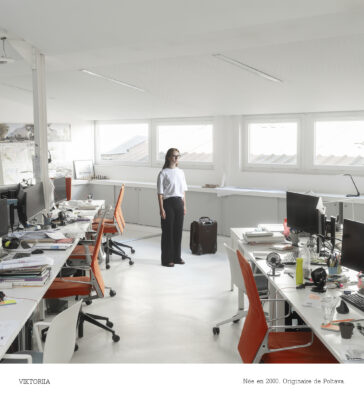

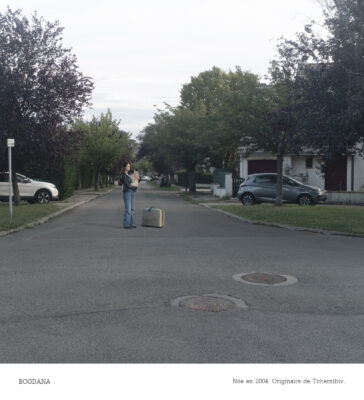

« Nowhere Is Everywhere » présente des réfugiés, hommes, femmes, enfants qui, pour la plupart, ont tout perdu, tout laissé derrière eux, certains ne reverront sans doute jamais leur pays natal.

Arrachés à leur monde, exilés, ils doivent se reconstruire dans un lieu qu’ils ne connaissent pas, qu’ils n’ont souvent pas même choisi, apprendre à nouveau, trouver de nouveaux repères. Langue, travail, administration, autant de défis, autant de nouvelles sources d’angoisses et d’isolement.

Les pathologies engendrées par cet exil forcé sont multiples. Le mal du pays est bien sûr la première à laquelle on pense, devoir quitter son pays de façon si précipitée ne laisse personne indemne. S’y ajoutent la nostalgie, la peur, l’impuissance, la colère, la tristesse.

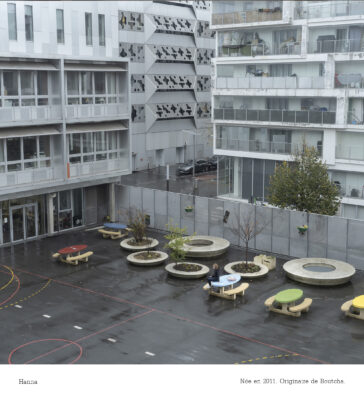

Puis il y a ce sentiment de solitude, d’isolement. La solitude face à sa famille, à ses amis que l’on ne voit plus, que l’on a perdu ou dont on n’a plus que peu ou pas de nouvelles. L’isolement face à son passé, sa vie d’avant. La solitude face à son nouveau quotidien, le sentiment de n’être à sa place ni ici ni ailleurs. Cette solitude qui vous habite, qui vous ronge tel un cancer.

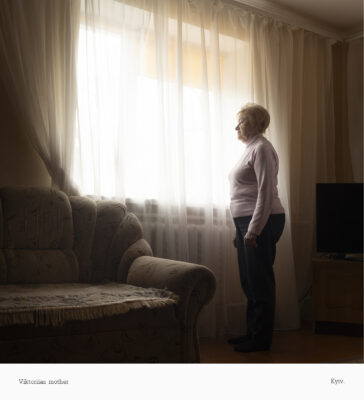

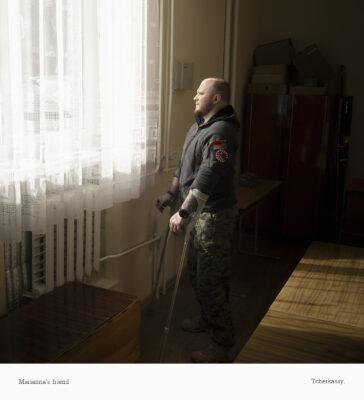

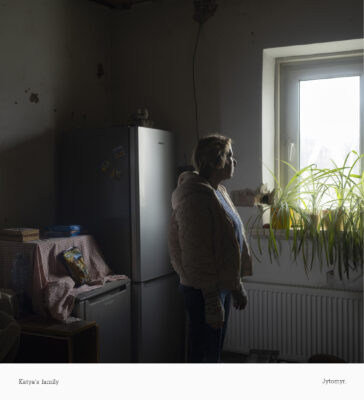

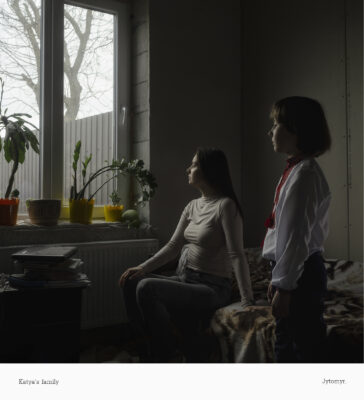

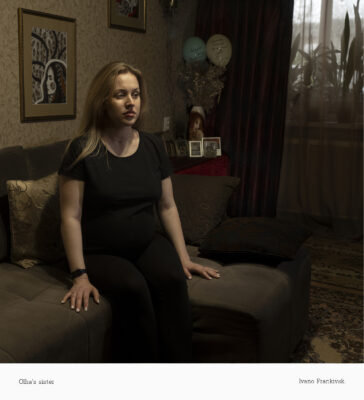

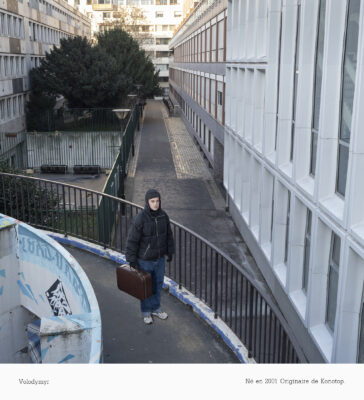

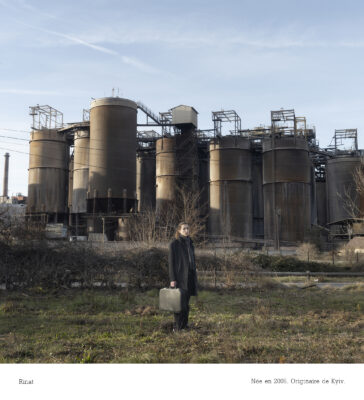

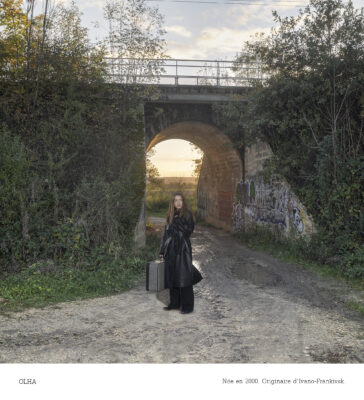

Mon travail ne cherche pas à témoigner des nouvelles conditions de vie de ces personnes. Il a pour intention de mettre en lumière la solitude, l’isolement qui les habitent et tendent à gagner en intensité au fil du temps pour certains d’entre eux.

Aussi, je les présente seuls, décontextualisés, face à eux-mêmes, face à l’immensité de ce qu’ils ont à accomplir. Car même si l’on est entouré, on reste seul face à ses traumatismes intérieurs et à ce déracinement.

Comme téléportés dans un nouveau monde qu’ils découvrent, seuls face aux défis qui sont désormais les leurs et qu’il leur faut affronter quotidiennement, face à leur passé, tout en devant cohabiter, pour certains d’entre eux, avec le sentiment qu’ils ont abandonné leur patrie, leurs proches, leurs amis, tels des déserteurs, ou pire, des ennemis.

Les images, mises en scène, illustrent plutôt qu’elles ne témoignent, la photographie envisagée comme hyperbole d’une réalité souvent ignorée.

L’image, pour peut-être s’accepter un peu plus, pour traduire avec ses moyens propres ce que l’on ressent et que l’on ne peut exprimer par des mots que souvent vos interlocuteurs ne comprennent pas.

Une image pour raconter.

Entre résilience et souffrance ces photographies nous interrogent aussi sur notre regard face aux réfugiés, face à ces gens dont nous ne connaissons rien et dont le sort et l’histoire les ont contraint à quitter leur patrie ; ces personnes dont notre regard se détourne aussi souvent sans chercher à connaitre ou à comprendre.

Mars 2024 : apres un an de travail avec les réfugiés il apparait de plus en plus clair pour moi qu’un élément manque à ma réflexion, à mon travail. Fréquenter ces réfugiés m’amène naturellement à m’interroger et à m’intéresser à leurs proches, à ceux qui sont restés.

Qu’en est il de voir un membre de sa famille partir à l’étranger, tout recommencer à zéro, dans un environnement que ni l’un ni les autres ne connaissent.

Ce sentiment du lointain, de l’inconnu, l’absence.

Une refugiée me disait « après deux ans en France j’ai changé, mais ma ville elle n’a pas changé si ce n’est le cimetière qui s’est considérablement rempli ; je ne m’y sens plus à ma place »

Reflétant une réalité établie je m’interrogerai sur l’évolution de ces destins ; ceux partis dont les vies sont bouleversées par le départ mais aussi par la vie dans un autre pays, une autre culture, une autre société, par l’inquiétude quotidienne de voir leurs proches touchés par l’horreur de la guerre et ceux restées, faisant face au quotidien aux difficultés de la guerre, à la peur, à l’absence et à la séparation.

J’éprouvais ce besoin d’aller à la rencontre des familles et proches des réfugiés que je photographiais depuis un an.

Je décidais donc de partir en Ukraine à leur rencontre.

Il sera question de photographier dans tout le pays les familles ou les proches des réfugiés sujets du premier volet, faisant ainsi le pont entre deux mondes séparés par la guerre.

Je partais donc avec ma voiture et mon matériel afin de pouvoir continuer à travailler de la même façon, éclairer mes scènes, mettre en scène ces personnes restées en Ukraine afin de pouvoir illustrer mon propos.

About

February 24, 2022, Russia launches a military offensive against Ukraine, attempting to invade it.

Thousands of Ukrainians are leaving their country in search of a land of asylum. France is one of them.

July 2022, I leave Paris to settle in Nice. At the same time, a Ukrainian family fleeing the war moved in on the landing opposite, my new neighbors. This meeting touched me by directly confronting me with the condition of these people, forced to flee their country, their loved ones, their roots, their daily life.

“Nowhere Is Everywhere” presents refugees, men, women, children, most of whom have lost everything, left everything behind, some will probably never see their native country again.

Torn from their world, exiled, they must rebuild themselves in a place that they do not know, that they often have not even chosen, learn again, find new benchmarks. Language, work, administration, so many challenges, so many new sources of anxiety and isolation.

The pathologies caused by this forced exile are multiple. Homesickness is of course the first thing that comes to mind, having to leave your country in such a hurry leaves no one unscathed. Added to this are nostalgia, fear, helplessness, anger, sadness.

Then there is this feeling of loneliness, of isolation. Loneliness when faced with your family, with your friends that you no longer see, that you have lost or of whom you have little or no news. Isolation from your past, your life before. Loneliness in the face of his new daily life, the feeling of not being at your place either here or elsewhere. This loneliness that inhabits you, that eats away at you like a cancer.

My work does not seek to bear witness to the new living conditions of these people. Its intention is to highlight the loneliness and isolation that inhabit them and tend to increase in intensity over time for some of them.

Also, I present them alone, decontextualized, facing themselves, facing the immensity of what they have to accomplish. Because even if we are surrounded, we remain alone in the face of our inner traumas and this uprooting.

As if teleported into a new world that they discover, alone facing the challenges that are now theirs and that they must face daily, facing their past, while having to coexist, for some of them, with the feeling that they abandoned their homeland, their loved ones, their friends, like deserters, or worse, enemies.

The photographs, staged, illustrate rather than testify, photography seen as hyperbole of a reality often ignored.

The image, to perhaps accept yourself a little more, to translate with your own means what you feel and which you cannot express in words that your interlocutors often do not understand.

An image to tell a story.

Between resilience and suffering, these photographs also question us about our view of refugees, of these people about whom we know nothing and whose fate and history have forced them to leave their homeland; these people from whom our gaze so often turns away without seeking to know or understand.

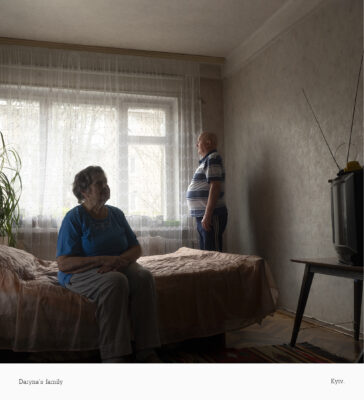

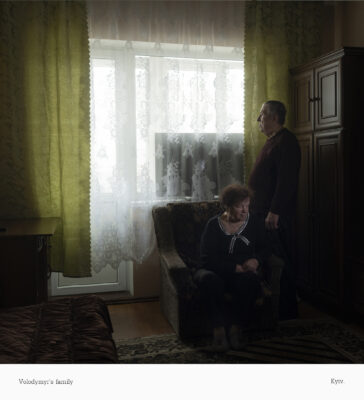

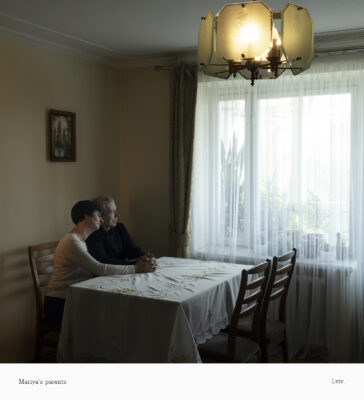

March 2024: after a year of working with refugees it appears more and more clear to me that an element is missing from my thinking, from my work. Meeting these refugees naturally leads me to wonder and take an interest in their loved ones, in those who stayed.

What is it like to see a family member go abroad, start everything from scratch, in an environment that neither of them knows?

This feeling of the distant, the unknown, the absence.

A refugee told me “after two years in France I changed, but my city has not changed except for the cemetery which has filled up considerably; I no longer feel at home there”

Reflecting an established reality, I will question the evolution of these destinies; those who have left whose lives are disrupted by departure but also by life in another country, another culture, another society, by the daily worry of seeing their loved ones affected by the horror of war and those who remained, making facing the daily difficulties of war, fear, absence and separation.

I felt this need to meet the families and loved ones of the refugees that I had been photographing for a year.

I therefore decided to go to Ukraine to meet them.

It will be a question of photographing throughout the country the families or loved ones of the refugees who were the subjects of the first part, thus bridging two worlds separated by war.

So I left with my car and my equipment in order to be able to continue working in the same way, to light my scenes, to feature these people who remained in Ukraine in order to be able to illustrate my point.

Про

24 лютого 2022 року Росія розпочала військовий наступ на Україну, намагаючись її захопити.

Тисячі українців покидають свою країну в пошуках притулку. Франція є однією з приймаючих країн.

У липні 2022 року я переїжджаю з Парижу до Ніцци. У той самий час українська родина, що також втекла від війни, поселяється навпроти і стає моїм новим сусідом. Ця зустріч вразила мене, зіштовхнувши з реальністю життя людей, які змушені залишити свою країну, близьких, коріння та, з рештою, своє щоденне життя.

«Nowhere Is Everywhere/Ніде і Всюди» проєкт, який представляє біженців – жінок, чоловіків, дітей, які, здебільшого, втратили все, залишили все позаду, а деякі з них, можливо, ніколи більше не побачать свою рідну країну.

Вирвані зі свого світу, біженці, вони повинні відновлювати своє життя в місці, яке їм незнайоме, часом, навіть, яке вони не обирали, їм треба вчитися заново знаходити нові орієнтири. Мова, робота, адміністративні питання – це нові виклики, нові джерела тривог та ізоляції.

Патології, викликані цією вимушеною еміграцією, є численними. Ностальгія за батьківщиною, звичайно, перше, шо спадає на думку, адже вимушений поспішний від’їзд з рідної країни не залишає нікого байдужим. До цього додаються ностальгія, страх, безсилля, гнів, смуток.

Потім виникає відчуття самотності, ізоляції. Самотність у стосунках з родиною, з друзями, яких більше не бачиш, яких втратив або з якими вже майже не спілкуєшся. Ізоляція від свого минулого, від свого життя до цього моменту. Самотність у новій буденності, відчуття, що ти не на своєму місці ні тут, ні там. Ця самотність, що проникає в тебе, що зжирає з середини, як рак.

Моя робота не має на меті засвідчити нові умови життя цих людей. Вона має на меті висвітлити самотність, ізоляцію, яка їх охоплює і для деяких з них стає все інтенсивнішою з часом.

Також я представляю їх самих, поза контекстом, сам на сам з собою, перед величезністю всього того, що їм належить тепер здійснити. Адже навіть якщо нас оточують люди, ми все одно залишаємося наодинці зі своїми внутрішніми травмами та цим викоріненням.

Наче телепортовані в новий світ, який вони відкривають для себе, наодинці перед викликами, які тепер стали їхніми і які вони повинні долати щодня. Зіткнувшись зі своїм минулим, деякі з них змушені співіснувати з відчуттям, що вони покинули свою батьківщину, своїх близьких, своїх друзів, як дезертири, або, що ще гірше, як вороги.

Ці знімки – ілюструють, а не свідчать. Фотографія розглядається як гіпербола реальності, яку часто ігнорують.

Знімок — щоб, можливо, трохи більше прийняти себе, щоб передати за допомогою власних засобів те, що відчуваєш і що не можеш висловити словами, які часто не розуміють твої співрозмовники.

Знімок, щоб розповісти.

Між стійкістю і стражданням ці фотографії змушують нас задуматися також про наш погляд на біженців, на цих людей, яких ми не знаємо і чия доля та історія змусили їх покинути свою батьківщину; цих людей, від яких ми часто відвертаємо свій погляд, не намагаючись дізнатися чи зрозуміти.

Березень 2024 року: після року роботи з біженцями для мене стає все більш очевидним, що в моєму міркуванні, в моїй роботі бракує одного елементу. Спілкування з цими біженцями природно спонукає мене задуматися і зацікавитися їхніми близькими, тими, хто залишився.

Зрозуміти, що означає бачити, як член твоєї родини їде за кордон, починає все заново, в середовищі, яке не знайоме ні їм, ні тобі.

Це відчуття далекого, невідомого, відсутності.

Одна біженка сказала мені: «Після двох років у Франції я змінилася, але моє місто не змінилося, якщо не брати до уваги значно заповнене кладовище; я більше не відчуваю, що належу до нього».

Відображаючи усталену реальність, я розмірковуватиму над розвитком цих доль: тих, хто виїхав, чиї життя змінилися через від’їзд, а також через життя в іншій країні, в іншій культурі, в іншому суспільстві, через щоденне занепокоєння про своїх близьких, які стикаються з жахами війни; і тих, хто залишився, щодня стикаючись з труднощами війни, страхом, відсутністю і розлукою.

Я відчував потребу зустрітися з сім’ями та близькими біженців, яких я фотографував протягом року.

Тож я вирішую поїхати в Україну, щоб зустрітися з ними.

Йтиметься про фотографування по всій країні сімей або близьких біженців – героїв першої частини, створюючи таким чином міст між двома світами, розділеними війною.

Я вирушив на своїй машині з обладнанням, щоб продовжити працювати таким самим чином, освітлювати свої сцени, ставити в центр уваги тих, хто залишився в Україні, щоб проілюструвати свою думку.